Reputation

Steve Jobs had the reputation of a hot-tempered manager throughout his life.

The Mac II (photo: Alexander Schaelss, GNU FDL 1.2 license) Microsoft licenses some of the Mac's technology in order to develop Office for Mac. Later that year, the company releases Windows 1.01. This article presents a timeline of events in the history of 16-bit x86 DOS-family disk operating systems from 1980 to 2020. Non-x86 operating systems named 'DOS' are not part of the scope of this timeline. Also presented is a timeline of events in the history of the 8-bit 8080-based and 16-bit x86-based CP/M operating systems from 1974 to 2014, as well as the hardware and software. January 24: Mac OS 7.6, the first part of Apple's new OS strategy, is released exactly 13 years after the introduction of the Macintosh. January 26: Steve Jobs, back as an 'advisor' due to the NeXT deal, announces the future of Rhapsody, Mac OS 8, Allegro, and Sonata, the Mac, NeXT, and Apple in general at Macworld Expo.

As early as 1987, the New York Times wrote: 'by the early 80's, Mr. Jobs was widely hated at Apple. Senior management had to endure his temper tantrums. He created resentment among employees by turning some into stars and insulting others, often reducing them to tears. Mr. Jobs himself would frequently cry after fights with fellow executives'.1

Some twenty years later, Michael Wolff's description of Jobs was little different: 'There's the mercurialness; the tantrums; the hours-long, dictator-like speeches; the famous, desperate, and transparent hogging of credit; and always the charismatic-leader complex [.], through which he has been able to seduce and, subsequently, abandon so many of the people he's worked with. He may be as troubled and unsocialized (and, too, as charismatic) a figure in American business life as anyone since Howard Hughes'.21 Yet, at the time of his passing, Jobs also had an outstanding 97% approval among Apple employees according to Glassdoor.22

The goal of this article is to explore that aspect of Steve Jobs in greater detail, and paint a broader and more accurate picture of what kind of manager he was.

What did Steve Jobs do at Apple?

Deadline (1982) Mac Os Download

Steve Jobs was not your typical Silicon Valley CEO. Unlike most tech companies founders, he had neither any engineering experience nor any business training. After all, he dropped out of college after one semester! Few people know that Steve Jobs was never CEO of Apple in his first run there: the company was run by older executives and investors, and Steve Jobs actually helped them hire an experienced, 'well-rounded' CEO in 1983, John Sculley. However, Jobs was kicked out of Apple by Sculley two years later and he watched him bring the company to naught during his tenure.

The lesson he learned from this painful experience was to trust his own beliefs and values, and completely disregard the conventional views on how to run a company, including the traditional duties of a CEO. He delegated those duties to members of his executive team, most notably his second-in-command and eventual successor, Tim Cook, and focused on what he was best at: creating products, recruiting, marketing, and of course, being the public face of the company. He described it in a 2004 interview: 'I get to spend my time on the forward-looking stuff. My top executives take half the other work off my plate. They love it, and I love it.'2 Ministate mac os.

Product Design

Steve Jobs had a very hands-on approach to product design, which was arguably the favorite part of his job. He famously often came down to the Industrial (i.e. hardware) Design lab to spend time with the designers team and give his opinion and guidance on their prototypes. This was also true of every software UI designer, who would quickly know what her über-boss thought of her work. In fact, product review sessions took up most of Steve Jobs's workday.

Jobs's reputation as a tech visionary originates not only from the reliable stream of breakthrough products that have come out of Apple in the last decade, but also from an observation from his closest colleagues. They recount countless times when he took a decision out of the blue, without any rationale, which turned out to be true. Ex-Apple employee Frederick Van Johnson explained it in the book Inside Apple3: 'Because he has that insight. You know, he's Steve. And you're like, how did [he] even know that? [He's] absolutely right. And it's not even blowing smoke. Normally, he has some sort of weird insight where he just knows.' Even Bill Gates acknowledged how impressed he was by that instinctual grasp of technology that Steve Jobs seemed to have.

Jobs himself also knew he was often right and made himself Apple's ultimate end user. He often used Henry Ford's quote on people wanting a faster horse to justify Apple's very scarce use of focus groups — but the truth was that he, the CEO, was the company's focus group. He thoroughly tested new products and came back with imperative feedback for the development team. If you've ever wondered why some Apple products, such as the Numbers spreadsheet program or the Xserve, seemed to stall in development, it's because Steve wasn't interested in them. This is actually a complaint that some Apple engineers have formulated over the years. Steve had his executive team focus intensely on 3 to 4 projects over a period of time — and if your project was outside their realm, you were out of luck.

Apple's public image

Steve Jobs had a unique talent for marketing in general, and advertising in particular. Just like his ability to anticipate the consumer's needs and wants, he could guess which marketing messages would work, and which wouldn't. He acknowledged this talent early on, as exemplified by the famous '1984' Macintosh ad that he insisted Apple ran, despite the board members' rising eyebrows. That commercial is now routinely called the best of the 20th century.

On his second tenure at Apple, Jobs would hold weekly meeting with his top marketing people, and the heads of TBWA's small division which only handles the Apple account, TBWAMAL. Says Lee Clow, the chairman of MAL and longtime friend of Steve Jobs: 'There's not a CEO on the planet who deals with marketing the way Steve does. Every Wednesday he approves each new commercial, print ad, and billboard.' This is how obsessed with Apple's image he was.

But it did not end with the ads and the marketing copies. Jobs also often called journalists to give his opinion on their articles on Apple, usually to complain about bad reviews or even the slightest criticism. Calling people up was actually very Jobsian, and he would also phone artists personally to get them to play at Apple events or in commercials, as well as competitors or prospective hires.

Recruiting

Hiring was actually one of his most important roles at Apple. He explained his philosophy in the 1980s already: 'A players hire A players,' he told the Mac team. 'B players hire C players. Do you get it?' He kept this philosophy that his job was to find the best possible people, to have them hire excellent people too, throughout his life. Railway riders mac os. 'My #1 job here at Apple is to make sure that the top 100 people are A+ players. And everything else will take care of itself. If the top 50 people are right, it just cascades down throughout the whole organization', he told Time in 199923. He personally oversaw the hiring of all top executives, and even some talented engineers or designers, calling them up directly to leverage his celebrity/icon status. Some famous examples of this are his trying to hire (or acquire) the Panic4 and Dropbox5 teams.

Jobs carried through this vision of the 'top 100' people at Apple by an annual event which he called the 'Top 100 retreat'. He took with them the Apple employees he felt were the smartest —not always the highest-ranked, mind you— and they all left to an undisclosed location where he would share the company's strategy for the coming year and the long term, so they could all brainstorm about it. The Top 100 created something of a caste at Apple: there were the 'Top 100' —the chosen ones that Steve would take with him in the proverbial life raft if he were to start Apple over again— and there were the others.

Deadline (1982) Mac Os Sierra

That vision thing

Of course, it was Steve Jobs who set the direction for all of Apple, together with his executive team (nicknamed 'ET'). The ET consisted of the top 10 executives of the company —in his later years, this would be COO Tim Cook, SVP of industrial design Jony Ive, SVP of iOS Scott Forstall, SVP of worldwide marketing Phil Schiller, SVP of Retail Ron Johnson, SVP of Internet services Eddy Cue, SVP of Mac hardware Bob Mansfield, and CFO Peter Oppenheimer. They met with Steve every Monday morning, and reviewed all aspects of Apple, discussing every issue and taking decisions. All the power at Apple was essentially concentrated in these meetings.

As Adam Lashinsky put it, Apple is 'a command-and-control structure where ideas are shared at the top'24 i.e. at the Monday executive meeting. All groups would work hard on presentations for the Monday meeting where they knew the fate of their product was at stake. Steve Jobs was famously open to the executives' arguments and ideas at these meetings. For example, they convinced him (after a long while) to open the iPhone platform with the App Store. But once a decision had been taken, there was no discussion in the rest of the company: they had to execute.

The best spokesman in the world

Steve Jobs was famous for his magnetic charisma and incredible showmanship, which he demonstrated at every Apple event. Although they seemed unrehearsed, these events were rehearsed and rehearsed several times over, and preparing for them was a huge part of Jobs's job —as well as many people at Apple. See Steve on Stage for more details.

Top negotiator

Everybody knows Steve Jobs was a master showman and a product visionary —but few people know he was also a very harsh businessman. 'For most people, he'll go down in history as the guy who made technology user-friendly. But to people in business, he'll be remembered as the guy who only did deals where he had all the leverage —and used every bit of it. It's not enough that he wins. You have to lose. He's completely unreasonable', said one executive to Esquire6. His negotiation skills proved crucial to Apple's success, including when negotiating with the major music labels before the launch of the iTunes Store, and with the carriers to prepare for iPhone. Woz speculated he acquired those skills with his dad who bought parts on car dealerships. It's one of the areas where he will perhaps prove irreplaceable.

A million other things

Steve Jobs was often called the ultimate micro-manager. Indeed, in addition to the big roles described above, he also got involved with all parts of Apple —and no detail was too small not to matter to him. Here are three examples:

- he personally picked the caterer for Apple's cafeteria, Il Fornaio, calling his predecessor's menus 'dogfood'. Later, he made sure that the sushi bar offered 'sashimi soba', an original creation of his;

- he once called Google executive Vic Gundotra on a Sunday morning to change the yellow gradient in the 10-pixel Google logo on the iPhone Map app25

- he personally picked the Italian marble to be used in the NY SoHo Store, and insisted that a sample was sent to Cupertino, so he could inspect the veining in the stone26

Apple employees have hundreds do examples of such dedication (some call it 'pain in the butt'). You can read some more on the Anecdotes page.

Steve at Pixar

Steve Jobs was Pixar's main investor for exactly twenty years, minus one week: he incorporated it on Feb 6, 1986, and sold it to Disney on Jan 24, 2006. However, his involvement with the company varied greatly throughout his life. Until 1993, he was mostly involved with NeXT, as an early employee recalled: 'Steve was never involved in the day-to-day at Pixar [.]. There were large stretches of time, even in Richmond, where we never saw him around. (Someone spotted him up there one day driving around, trying to remember where our driveway entrance was.) NeXT and, later, Apple, kept him pretty busy.'7 His most hands-on period with Pixar was between 1995 and 1997, between the finishing touches on Toy Story and his comeback to Apple.

In 1999, he told Time 'There's not a day that goes by that I don't do stuff for Pixar, even if I'm not physically there. And there's not a day that I'm at Pixar that I don't do stuff for Apple'8, which sums up his involvement with the animation studio quite well. He was mostly involved in major business decisions, such as the negotiation of deals with Disney or the building of the Emeryville campus (although he became obsessed with that campus when it was built in 1999-2000). 'The Holy Grail for Pixar is releasing one product—a movie-a-year, and as CEO I might make three really critical decisions a year, and they are very hard to change', said Jobs in 2003.9

After Pixar was acquired by Disney in 2006, he became a prominent board member of the Walt Disney Company, but that didn't take him nearly as much time as being CEO of Pixar. https://ladyfataegamesfamily-casino.peatix.com.

The culture he has created at Apple

Organization

As explained above, Steve Jobs was told to let 'more experienced' managers run the company in his first tenure at Apple —which led to his resignation and the John Sculley debacle. That is not to say that he had no business sense at the time: in his book about Jobs, Jay Elliot recalls how he used to 'dream of the time that Apple could slash its way through to a much simpler management structure, with fewer approval levels, fewer people needing to sign off on every decision. He used to tell me, 'Apple should be the kind of place where anybody can walk in and share his ideas with the CEO'.'20 Although he could never really apply his big dreams at NeXT, which remained small, he did so at Apple after his comeback.

The first priority for Steve when he came back was simplicity: 'The organization is clean and simple to understand, and very accountable. Everything just got simpler. That's been one of my mantras -- focus and simplicity', he said in 1998.10 In other words, the responsibilities of every employee are very clear. For each project, and every task in that project, there will be someone accountable, a so-called DRI (directly responsible individual) who will be congratulated or blamed depending on their task's success or failure.

Vladimir llyich Jobs, for The Wall Street Journalby Ken Fallin

On the executive level, Steve Jobs was very explicit that everyone's job was constantly on the line. In his book Inside Apple, Adam Lashinsky explained Steve's parable of 'the VP and the janitor': he imagines his trash not being emptied for some time. When he confronts the janitor, he is told that the keys to the locks have been changed and the janitor can't do his job anymore. Then he says to the VP: 'When you're the janitor, reasons matter. Somewhere between the janitor and the CEO reasons stop mattering, and that Rubicon is crossed when you become a VP.'11 That is not say that each manager is held accountable on a financial level. On the contrary, the only manager with a 'P&L' (i.e. their own profit center) is the CFO, so as not to create fiefdoms: there is one bottom line at Apple. General managers are even avoided, VPs being generally specialized engineers that have been promoted — with sometimes little to no business training.

As for product teams, they have to remain small —for example, there were only two programmers in charge of the original Safari for iPad. The deadlines and the objectives assigned to those teams are in general very precise and in the relative short term. Again, it's all about results and execution: ideas have been debated and decisions taken by the ET earlier. As opposed to traditional product management, products don't pass from team to team: they are worked on in parallel, all at once, in some sort of organic process punctuated by cross-team meetings.

All these business practices: the smaller teams, the lack of financial responsibility for departments, the very simple hierarchy, the organic development process, even the financial compensation (stock options) were put into place by Steve Jobs to keep a startup mentality at Apple. He even called the company 'the world's biggest startup' in 2010, proud of the fact that the company kept reinventing itself while its competitors failed to do so. In many ways, his management philosophy, quite different from classical business training, was a total success.

Secrecy

Flaming sevens slots. Steve Jobs learned how important secrecy was for a technology company during the development of the Macintosh. The product was originally supposed to be out in 1982, and Steve Jobs started talking about it around that time — but the release date kept slipping and slipping, until it was finally set in 1984. By then, Jobs had already leaked most of the revolutionary product's features to the press, and the surprise was much lessened. He learned his lesson when he started NeXT two years later. The NeXT Cube was very late, too, but no one could tell, because no release date was ever pre-announced; and the media covered the introduction amply, since the features of the Cube had remained secret.

Jobs has enforced this rule as strictly as he could during his second tenure at Apple. The company had become one of the leakiest in Silicon Valley, and he made sure everyone understood this was over when he came back. It is fair to say he instilled a culture of fear to prevent Apple employees to talk about their work, on the outside, but oftentimes also among themselves.

The secrecy from outsiders has obvious motives, such as leaving competitors in the dark, not having to apologize for a late product, and of course the huge free publicity that come from both speculation and the sensational release of new products. Every employee knows this is worth millions of dollars, and that a leak would cost them their job and severe trials. Apple actually distills false information to some of its employees to track down the source of leaks, and supposedly keeps a special teams dedicated to just that: tracking leaks. It enforces these rules as hard as it can with all their business partners such as part suppliers or developers, who were sometimes asked to protect the secret beyond reason.12

Secrecy was enforced within the company, too, i.e. most Apple employees have no idea what their colleagues are working on. Apple is 'the ultimate need-to-know culture', an environment where engineers are only told what they need to know to get their job done. For example, the iPhone had only been seen by about thirty people in the company before Steve Jobs unveiled it in January 2007. The rationale is to further enforce the secrecy to outsiders, but also to avoid politics: 'Below a certain level, it is difficult to play politics at Apple, because the average employee doesn't have enough information to get into the game. Like a horse fitted with blinders, the Apple employee charges forward to the exclusion of all else', writes Adam Lashinsky in Inside Apple.

Strive for perfection

The word 'perfectionist' has become a cliché in the corporate world —but it was not a buzz word for Steve Jobs, who genuinely obsessed over the smallest details. Most employees working on Apple products would sooner or later be exposed to his feedback, either directly or through their boss after a Monday executive meeting, and this feedback would usually come in one of these three formats: 'it's great', 'it's not bad, but change this, this, and that' or, usually (especially for the first version put forward) 'it sucks', 'it's shit', 'this is a D' or some other expletive.

This attitude was often heralded as proof that Steve Jobs was a 'jerk'. Yet how come Apple employees are so loyal, and the company so efficient, with a jerk at the top? Most colleagues of Jobs described him as 'brutally honest' and never willing to settle for anything than the absolute best. In other words, nothing was ever 'good enough' —it had to be perfect. Even though Steve Jobs interacted with no more than about 100 employees, this attitude rippled through the whole company —also by fear. An ex-Apple employee writes: 'when Steve was pissed off about something, it got fixed at a pace I've never seen then or since in my professional life. I guess some people reacted that fast out of fear, but more directly, you would get used to refusing to accept anything but flawless execution.'

Indeed, most employees felt as if Steve Jobs was always behind them, watching their work and making sure it was up to Apple's standards: 'You might go awhile without seeing him. But you are constantly aware of his presence. You are constantly aware that what you're doing will either please or displease him. I mean, he might not know who you are. But there's no question that he knows what you do. And what you're doing. And whether he likes it or not' said an Apple employee. Another said in Inside Apple: 'You can ask anyone in the company what Steve wants and you'll get an answer, even if 90 percent of them have never met Steve.'

Employees working on product development at Apple were used to other demands of Steve that few companies are familiar with. This included his obsession to saying no more often than yes when it came to a product design or features i.e. the absolute necessity to focus. They were also ready to start over a product from scratch when Jobs and the ET felt they were on the wrong track: this happened in 2006 with the original iPhone. And even executives accepted that their teams compete if the end goal, the product, was going to benefit. For example, Scott Forstall's OS X team and Tony Fadell's iPod team both used their best people to develop an operating system for iPhone, because Jobs hesitated which one to pick. Eventually, iPhone used OS X, and the iPod people had worked for months for no concrete outcome. But the end choice was the best, and such willingness to sacrifice time and money for a better product was natural at Apple under Jobs.

Steve Jobs's real management style

A common refrain heard when talking about Steve Jobs's management style is that Apple employees are so scared of him than they avoid getting into the elevator with him because they worry to lose their job during the trip. It is likely this must have happened once, probably in 1997 when Steve Jobs was asking every employee to defend their job's contribution to the company, but it certainly wasn't commonplace. https://downloadtraveler.mystrikingly.com/blog/decay-mac-os.

It is true, however, that Jobs was hot tempered, could easily start shouting at his employees and calling their work shit, and reduce them to tears. But he was not just cruel and brutal: he could also be a total charmer and make his colleagues feel like geniuses (this is how he hired most of them actually). While at NeXT, his employees dubbed this swift change of attitude 'Steve's hero/shithead roller-coaster', a nice metaphor for the binary view with which Jobs described the world, and how he treated his fellow staff. People often wondered why he felt necessary to resort to derogatory remarks and mean insults when he was disappointed with someone's (hard) work. His biographer Walter Isaacson asked him, to which he replied 'that's just who I am'. He was indeed very self-aware —he once called Fortune's editor to complain about a piece about him, only to say 'Wait a minute, you've discovered that I'm an asshole? Why is that news?'

Most people who worked closely with Steve have a theory on why he acted this way: it was to extract the best of them, make them do the best work they could. And in fact, most agreed they achieved feats they did not think they were capable of under his pressure. The psychological mechanism at work was that once you had been praised by Steve, then insulted, you would work twice harder to earn back his favors. As early as the 1980s, the Mac team members all agreed that without Steve's strong will, there probably wouldn't have been a Mac. More recently, Apple employee Mike Evangelist wrote: 'I was incredibly grateful for the apparently harsh treatment Steve had dished out the first time. He forced me to work harder, and in the end I did a much better job than I would have otherwise. I believe it is one of the most important aspects of Steve Jobs's impact on Apple: he has little or no patience for anything but excellence from himself or others.'13

In his dealings with the executive team, though, he seemed more open to arguments — heated arguments, but arguments nonetheless. In fact, he loved to argue, and one of the defining characteristics of his famed 'reality distortion field' was, according to Andy Herzfeld, Steve's habit of 'throw[ing] you off balance by suddenly adopting your position as his own, without acknowledging that he ever thought differently'.14 He wanted to explore every facet of an argument before making his mind. Such arguments were no fun and games, however: if you stood up against him, you'd better come prepared to defend your stance, because he would not suffer a fool. Mike Evangelist called it his 'logical flaw detector, his uncanny ability to see thru any BS and to instantly zero in on the weak point(s) of any argument. [.] He grasps the salient points of any situation faster than anyone I've met, and if you can't keep up that's not his problem.'15

Steve Jobs explained the reason for his impossible demands to Steven Levy, as early as 1983: 'We have an environment where excellence is really expected. What's really great is to be open when [the work] is not great. My best contribution is not settling for anything but really good stuff, in all the details. That's my job — to make sure everything is great'.16 The best description probably should be attributed to Jony Ive, who said in the tribute ceremony that Apple held two weeks after Steve's passing: 'it cost him most. He cared the most. He worried the most deeply. He constantly questioned: is this good enough? Is this right? And despite all his successes, all his achievements, he never presumed, he never assumed that we would get there in the end. And when the prototypes failed, it was with great intent, with faith, he decided to believe we would eventually make something great. [.] So his I think was a victory for beauty, for purity, and as he would say, for giving a damn.'

Steve's workday

In the last extensive recorded interview he ever gave, at the D8 conference in 2010, Steve Jobs was asked by Kara Swisher 'What do you do all day?' A naive question it seems, but one that many observers ask themselves, given both Steve's few business implications compared to a typical CEO, and his absolute dedication to a million things that have nothing do with the job of CEO.

Steve Jobs answered that question several times throughout his career. In 1999, he said to TIME: 'I'm a good morning person. I like it early in the morning. I wake up six-ish. About 10 years ago I put in a T1 to my house. I'm actually getting ready to put a 45MB fiber to my house, because I want to find out what that will be like, because everybody's going to have that someday. But I have a pretty sophisticated setup; whether I'm at Apple or at Pixar or at my home, I log in and my whole world shows up on any of those computers. It's all kept on a server. So I carry none of it with me, but wherever I am, my complete world shows up, all my files. Everything. And I have high speed access to all of it. So my office is at home too. And when I'm not in meetings, my work is fundamentally on email. So I'll work a little before the kids get up. And then we'll all have a little food and finish up some homework and see them off to school. If I'm lucky I'll stay at home and work for an hour, because I can get a lot done, but oftentimes I'll have to come in. I usually get here about 9. 8 or 9. Having worked about an hour or half or two at home.'17

A huge part of his job was indeed email. His could be sent to Apple employees, where it was famous that a message whose subject was 'STEVE REQUEST' would get immediate attention. But Steve also read the hundreds of emails he got from various customers everyday, sent to his public address sjobs@apple.com. He explained it to Time: 'All these customers email me all these complaints and questions, which I actually have grown to like. It's like having a thermometer on practically any issue. If somebody doesn't flush a toilet around here, I get an email from Kansas about it. Sometimes I can get about 100 or more of those a day from people I will never meet. But I zing 'em around, and it's good to keep us all in touch.'

He also described his Monday meetings in 2008, to Fortune: 'What we do every Monday is we review the whole business. We look at what we sold the week before. We look at every single product under development, products we're having trouble with, products where the demand is larger than we can make. All the stuff in development, we review. And we do it every single week. I put out an agenda —80% is the same as it was the last week, and we just walk down it every single week. We don't have a lot of process at Apple, but that's one of the few things we do just to all stay on the same page.'18 Although the Monday executive meetings were probably the most important of the week, he also had long sessions on Wednesday afternoons with his ad agency TBWAMAL and his top marketing people, such as SVP Worldwide Marketing Phil Schiller.

Finally, the Walter Isaacson bio revealed that one of his favorite pastimes was to hang out in the Industrial Design's lab in the afternoon, where Jony Ive and his team of designers worked on prototypes of future hardware products: 'When Steve comes in, he will sit at one of these tables', said Ive. 'If we're working on a new iPhone, for example, he might grab a stool and start playing with different models and feeling them in his hands, remarking on which ones he likes best. Then he will graze by the other tables, just him and me, to see where all the other products are heading. He can get a sense of the sweep of the whole company, the iPhone and iPad, the iMac and laptop and everything we're considering. That helps him see where the company is spending its energy and how things connect.'19

Jony Ive was Jobs's only soulmate at Apple, probably because of his aesthetic, artistic sensibility. Jobs deliberately put Industrial Design on top of every other division at Apple, to ensure that the most beautiful hardware prototypes eventually turned into actual products, without being twisted and deformed by engineers. He explained it to Isaacson: '[Jony Ive] understands that Apple is a product company. He's not just a designer. That's why he works directly for me. He has more operational power than anyone else at Apple except me. There's no one who can tell him what to do, or to butt out. That's the way I set it up.'

Companies working on iPad software before the product was for sale testified that 'even after the formal introduction of the iPad, [they] were required to keep it under padlock and key, with the key turned by Apple every night', Developer offers glimpse inside Apple's secrecy efforts, Josh Ong, Apple Insider, 9 Sep 2011 ↩

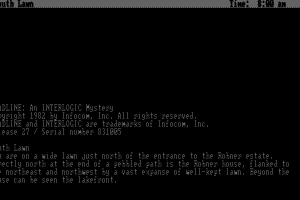

Available Platform: DOS

Deadline is a text adventure published by Infocom in 1982. It was written by Marc Blank, one of the principal authors of Zork. The game was initially released for the Apple II, At.

| Year | 1984 |

| Genre | Adventure |

| Rating | 87/100 based on 5 Editorial reviews. Add your vote |

| Publisher | Infocom |

| Developer | Infocom |

| OS supported | Win7 64 bit, Win8 64bit, Windows 10, MacOS 10.6+ |

| Updated | 2 December 2020 |

Game Review

Deadline is a text adventure published by Infocom in 1982. It was written by Marc Blank, one of the principal authors of Zork. The game was initially released for the Apple II, Atari 8-bit, and TRS-80. Then later for the Commodore 64, MS-DOS, Macintosh, TI-99/4A, and several other platforms.

Blank wanted to try a different genre, after the three fantasy chapters of Zork. With Deadline, he tested his writing skills with a hardboiled/crime interactive fiction, and the result was excellent. The story is a classic. The rich and famous entrepreneur Marshall Robner was found dead in his library - the door closed from the inside. Apparently, it's an overdose of antidepressants, and the police are going to close the case as a suicide. But Robner's lawyer is not convinced, and he asks you, a famous detective, to investigate. You have exactly 8 hours to find the truth, exploring the house, and talking with the possible suspects.

What is new and exciting about the Deadline is that time actually passes (one minute per turn), and things 'happen.' The reality changes around you. You don't have the classic troll waiting for you at the bridge with his puzzle, for an infinite time, until you solve it. In Deadline, you must be in the right place at the right time. For example, if you are near a telephone at 9:07, you will hear it ringing, and you can type ANSWER TELEPHONE. Doing so, you will listen to Mrs. Robner - that picked up the line from another phone - talking with someone.

Similarly, if you are on the front door around 10 am, you can intercept the postman and read a very interesting letter. At this point, you should have understood that Deadline was (it still is) a very innovative game. In classic adventures, you could be stuck at some point for a long time because you cannot solve a puzzle. But as soon as you solve it, you will go ahead. Deadline instead is relatively short and small, and with no more than 50 different locations on the map, but often you will realize that you have just missed an important event, and you will have to restart. It's a game that must be played more than once, learning from your mistakes.

The other significant change introduced with Deadline is the importance of the NPCs. Each one of them has his own personality and emotional state, which can change depending on what you do. That's why dialogues are so critical. Just like in modern Bioware games, your choices in the conversations will make a difference. In fact, Deadline introduces for the first time parse commands such as ASK person ABOUT another person or TELL person ABOUT another-person. If you want, you can also try something like 'MRS ROBNER, TELL ME ABOUT STEVEN.' It works.

But now enough with the spoilers. You have enough clues to realize that Deadline is clearly a fantastic game. Even if you have never played an interactive fiction, this one is worth trying. My suggestion is to download a tutorial, but use it only when strictly necessary. Happy investigation!

Review by: E. Bolognesi

Published: 13 September 2020 10:05 am American roulette payout.